What do researchers Dr. Alex Huang and Dr. Carl Allen have in common? Passion, curiosity, drive, brilliant ideas, a desire to help kids — the list goes on! And now there’s something else. They are both recipients of the first St. Baldrick’s Innovation Award. What do they want to do with this unique grant? Read on to find out.

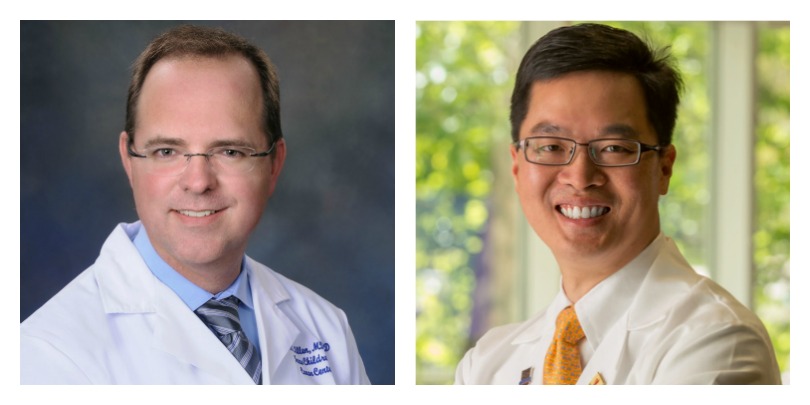

Dr. Carl Allen (left) is an associate professor at Texas Children’s Cancer Center and one of the investigators involved in the North American Consortium for Histiocytosis (NACHO), which received a St. Baldrick’s Consortium Grant. St. Baldrick’s researcher Dr. Alex Huang (right) is a professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and a 10-time shavee with St. Baldrick’s.

St. Baldrick’s researchers Dr. Alex Huang and Dr. Carl Allen work on different projects, in different labs about 1,300 miles away from each other.

Dr. Huang primarily studies how immunotherapy can help kids with cancer, while Dr. Allen studies Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis or LCH, which is caused by out-of-control immature white blood cells. The disorder can cause inflammatory tumors, damage organs and even cause brain degeneration in some patients.

The two researchers may work in different areas on different projects, but since the start of their careers in medicine, they’ve shared a goal — to help sick kids get better. And now they have something else in common.

A couple weeks ago, both researchers got an unexpected message from St. Baldrick’s Board and Scientific Advisory Committee member Jeff Lipton. They had each been granted a St. Baldrick’s Innovation Award.

Dr. Huang was visiting his family in Taiwan when he got the news. He felt both humbled and satisfied.

“We are very thankful that there is some confirmation and affirmation that what we’re doing is worth continuing,” he said.

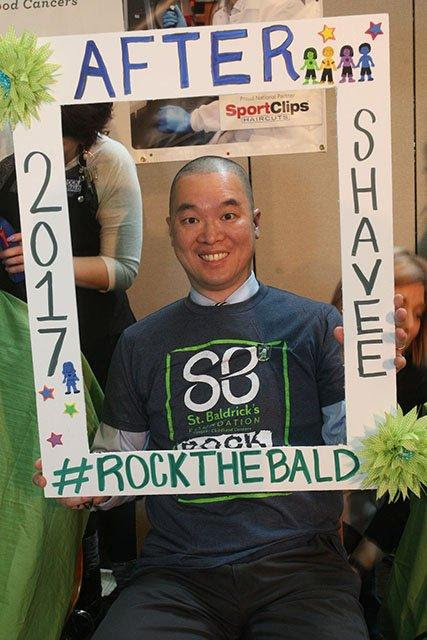

Dr. Alex Huang mugs for the camera after shaving his head with St. Baldrick’s to raise funds for lifesaving research.

What Dr. Huang and his lab is doing is a lot. With 25 people working in his lab, including two cancer survivors, Dr. Huang and his team are involved in a variety of pursuits. In Dr. Huang’s opinion, a multifaceted approach is what is needed to beat childhood cancer.

“We have five decades of experience showing that cancer cells are very, very smart. If you keep hitting cancer cells with a baseball bat, all the cancer cells will do is just put a baseball helmet on and they’ll be fine,” he said. “So, you’ve got to come at them at multiple angles to not allow them to develop resistance.”

Learn how Dr. Huang uses the movie series Star Wars to explain his research >

For instance, they are looking at how to stop the spread of osteosarcoma to the lungs by studying how certain immune cells, called macrophages, interact with the cancer cells in that environment. Essentially, they found that the macrophages and the cancer cells communicate and that relationship helps the cancer survive and continue to spread.

“We have now gone on to figure exactly what is going on between the tumor cells and the macrophages that allow them to have this communication,” he said. “We have pinpointed the communication molecules and it turns out that these molecules can be disrupted by FDA-approved drugs that are used now in multiple sclerosis and inflammatory bowel disease.”

Dr. Huang is now working to get a clinical trial off the ground to investigate this potential new therapy for kids with metastatic osteosarcoma.

In addition, he’s also studied how certain cancerous tumors – primarily pediatric brain tumors and rhabdomyosarcoma — protect themselves from the immune system and how those defenses can be overcome by inhibiting certain molecules. Promising drugs that inhibit these molecules are in clinical trials for use in adults, Dr. Huang said, and he’s working to have them tested in children’s cancers as well.

While Dr. Huang is figuring out how to attack cancer using the immune system, Dr. Allen is delving deeply into the inner workings of LCH to find personalized, targeted therapies to help kids with this disease.

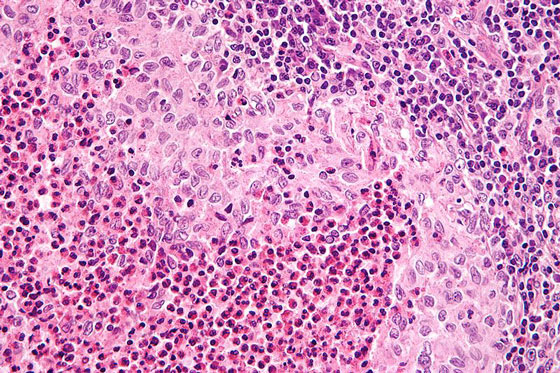

LCH as seen under a microscope.

With the rise of sophisticated gene sequencing technology and after decades of debate, LCH has only recently been considered as part of the cancer family. It’s just as common as pediatric acute myeloid leukemia, Dr. Allen explained, and yet so much about the disease is still unknown.

“One of the mysteries of LCH is that some kids will get just one or two lesions that aren’t particularly clinically significant and they might not even require chemotherapy to go away,” he said, adding that for others just minor surgery might be needed. “For other people, it’s like they have leukemia and they need high-dose chemotherapy for cure.”

Like Dr. Huang, Dr. Allen is taking a multifaceted approach to figuring out what makes LCH tick and how to treat it.

He’s studying different mutations found in LCH, how these mutations drive the disease and if different mutations correlate to better or worse outcomes in patients. He’s also questioning how the stage of differentiation of the ‘mother’ cell – or where the original, disease causing cell is in its journey to growing more specialized – might affect the extent of the disease.

“Part of the research is to prognosticate and to try to understand the disease better,” he said.

And in that quest for understanding, Dr. Allen and Dr. Huang got a surprise boost.

Like the Robert J. Arceci Innovation Award, this Innovation Award gives the researchers the freedom and funding to pursue out-of-the-box ideas with minimal strings attached — unlike traditional grants which come with restrictions and constraints.

“What the Innovation Award does is it really lets you chase the data in real time. It means that when we get a promising signal, we can jump on that as quickly as possible, do a few experiments to see if we think it’s going the right direction and then maybe that will lead to my next, more traditional grant,” Dr. Allen said. “This will really be a catalyst to help up sift through all these opportunities and data that we have and get enough pilot data to justify more sustained research.”

YOU make these grants possible. Fund lifesaving childhood cancer research today.

Read more on the St. Baldrick’s blog:

SBF

Tweets »

SBF

Tweets »