McKenna Claire was 7 years old when she was diagnosed with a rare brain tumor called DIPG. The McKenna Claire Foundation was established in her memory and in 2013, St. Baldrick’s partnered with the McKenna Claire Foundation to fund DIPG research, like the work done by Dr. Rameen Beroukhim at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute.

Honored Kid McKenna Claire was bright, spirited, and loved soccer and gymnastics. McKenna was full of grace, joy and grit through it all, even as her childhood cancer progressed and she could no longer run across a soccer field, jump on a trampoline, talk or swallow. She died just six months after her diagnosis with a rare, fatal type of brain tumor called DIPG – weeks before her birthday. She would have been 8 years old.

Learn more about McKenna and her cancer journey from her mom, Kristine >

Stories like this are why St. Baldrick’s researcher Dr. Rameen Beroukhim studies DIPG, otherwise known as diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. In fact, McKenna’s photograph hangs in his lab.

Dr. Rameen Beroukhim and his colleague Ofer Shapira write out ideas on the white board in their lab at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

In 2016, Dr. Beroukhim was the recipient of a St. Baldrick’s Research Grant with generous support from the McKenna Claire Foundation.

“DIPG may be the worst cancer imaginable, in that they are brain cancers that occur in children, often very young children and occur in a location that is absolutely essential for basic functions of life,” he said. “They are uniformly fatal and usually they kill children pretty quickly and our treatments are not very effective. One of the main reasons why we’re not able to come up with better treatments for this cancer is that we don’t understand it as well as we’d like.”

Dr. Beroukhim’s goal is to understand DIPG on the deepest level possible – the genomic level. In his research, he studies tissue samples from DIPG tumors to understand the mutations that take place within the tumor cells when a child goes through treatment. These mutations are the cancer’s way of protecting itself, so it can continue to grow.

“If we can figure out what those mutations are and devise treatments that either oppose those mutations or avoid those mutations, then we could enhance the effectiveness of our treatment,” he said. “That’s our goal, to really have a rational therapeutic approach where we understand what happened to the person’s tumor and then fix that.”

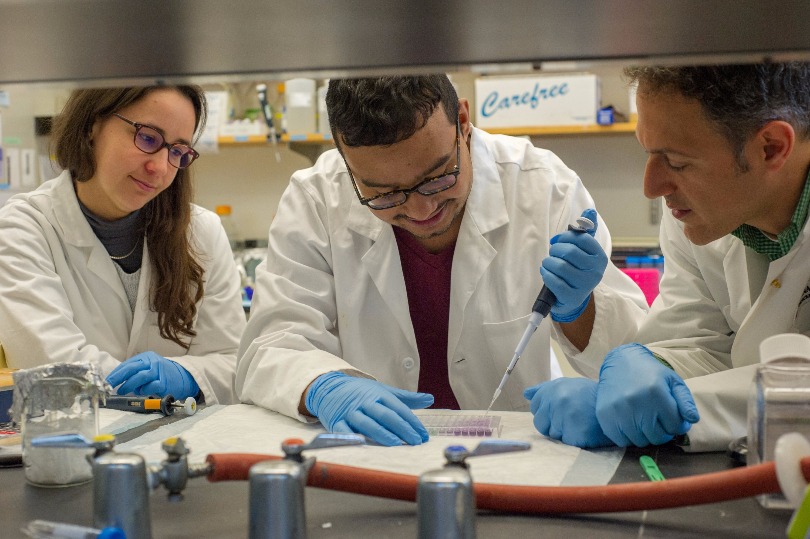

Dr. Rameen Beroukhim (right) watches his colleagues (from left) Melanie Pages and Prasidda Khadka work on samples in the lab.

So far, Dr. Beroukhim and his team have found multiple mutations, including one called PPM1D that looks promising and could be a target for a drug that’s already in development. The results are preliminary, but exciting and could mean big things for kids with DIPG.

“If we can understand how PPM1D is giving rise to tumors and how we can reverse its effects, that will hopefully translate into therapeutic options that we will be able to take to clinical trials,” the physician-scientist said. “I’m hoping that is true for PPM1D and I’m hoping that will be true for other genomic changes that we see in these tumors through the studies that are funded through the St. Baldrick’s award and other agencies.”

Thanks to the data he gathered during the St. Baldrick’s-supported study, Dr. Beroukhim was awarded a prestigious grant from the National Institutes of Health that will help him continue this work.

Without the support from St. Baldrick’s and the McKenna Claire Foundation, none of this would have happened.

“To get federal funding for that [a good idea] can be really difficult, because they want you to show them that you’ve already taken a few steps to understand that your idea is going to work. So, you need to generate that preliminary data. You can’t do that with federal funding,” he explained. “I think that’s where the St. Baldrick’s award helps us pursue sometimes risky ideas, but often very good ideas, to the point that we can then show, ‘Yes, there’s some likelihood that this is going to work out.’”

Dr. Rameen Beroukhim (left) smiles with his colleague Pratiti Bandopadhayay in the lab.

Dr. Beroukhim hopes that his research leads to more effective therapies for these fatal tumors and that understanding DIPG will eventually lead to a cure. Helping kids with cancer has been his mission since he was in medical school.

“You have people who are just walking around, doing fine, and then, all of a sudden, boom. They have this awful diagnosis. … That just got me. It caused a lot of dissonance for me. I thought, ‘I want to work toward trying to fix that problem,’” he said. “I think the archetype of that problem is with children with DIPGs, where you have young children who are healthy and vital children, surrounded by loving families. It’s upsetting.”

Now, with three kids of his own – one of them who is around McKenna’s age – the realities of DIPG hit close to home. Kids like McKenna drive him to find a cure.

“It’s just awful,” he said. “You really want to do something for them.”

Together we can take childhood back from cancer. Fund lifesaving research today.

Read more on the St. Baldrick’s blog:

SBF

Tweets »

SBF

Tweets »