Where is our very first St. Baldrick’s Fellow now? Still in the lab, that’s where! Meet Dr. Sharon Singh, the physician-scientist who was given the inaugural St. Baldrick’s Fellow Award in 2005. What does that monetary vote of confidence do for a new researcher and for the childhood cancer research field? It’s been 19 years and the results are in – read on to find out.

Dr. Sharon Singh currently works as a clinician, researcher, and associate professor at University of Michigan, C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital.

At the heart of it, Dr. Sharon Singh is a problem solver and for the last decade, the pediatric hematologist-oncologist has been working on the problem of childhood cancer. But she knows that the big problem of kids’ cancer can’t be solved only at the bedside of a patient – problem solvers like her need to be in the lab too.

And that is exactly what Dr. Singh is doing, thanks to a St. Baldrick’s grant given almost 20 years ago.

Dr. Singh was the first recipient of the St. Baldrick’s Fellow grant, an award aiming to provide doctors with training in research. She was nominated by her mentor, St. Baldrick’s board member and scientific advisor Dr. Jeffrey Lipton, back in 2005 when she was fresh out of residency and doing her fellowship at Cohen Children’s Medical Center in New York.

“I have always loved research, but not everyone who wants to do research gets that chance,” she said. “St. Baldrick’s giving me an opportunity like that made me feel really privileged – that they would choose me to be their first fellow.”

Dr. Singh used her Fellowship grant and a subsequent St. Baldrick’s Scholar award to work on a rare disease called DBA or Diamond Blackfan anemia. Dr. Singh studied how DBA works and why young patients with DBA have an increased risk of developing cancer.

In this burgeoning field of research, it was commonly thought that high levels of a protein called P53 caused DBA. But when Dr. Singh and her colleagues studied the cells closely, she found that may not be true in all cases. Instead, overexpression of P53 wasn’t found in some variations of DBA – it may be just one of many interactions that led to this disease.

Dr. Singh explained that scientists don’t understand exactly why young patients with DBA have an increased risk of cancer, however the same mutation seen in kids with DBA has now been found in some T cell leukemias found in children and B cell leukemias found in adults, possibly leading to new insight into those cancers.

“How does that [mutation] make the cancer behave differently? Are there new medicines that can target the cancer? I think more and more people will start studying the mutations that lead to DBA eventually and it could open up a whole new way to treat these cancers in children,” she said. “That’s what I’m hoping.”

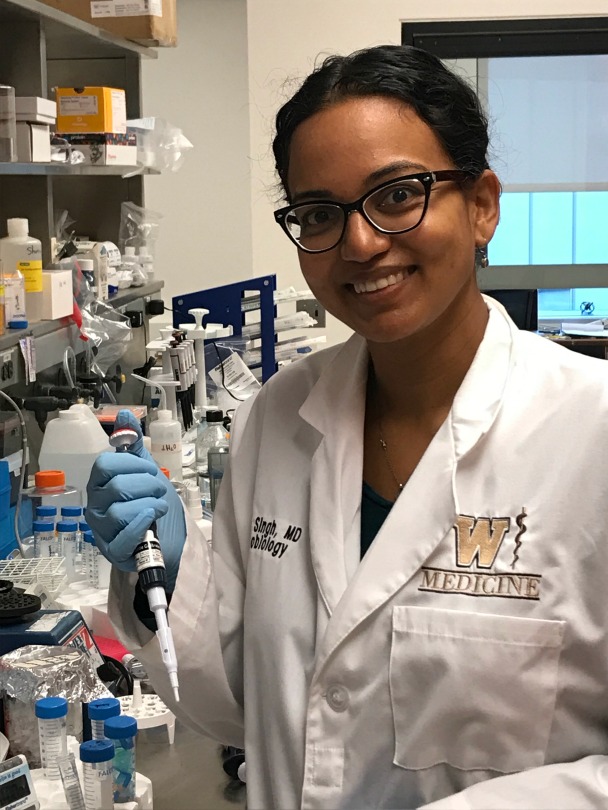

Dr. Sharon Singh during her time as a St. Baldrick’s Scholar, when she studied DBA. Kids with DBA generally get diagnosed at 2 months old and some kids require blood transfusions and even bone marrow transplants, while others aren’t affected and show no symptoms.

Dr. Singh is now an associate professor at University of Michigan, seeing patients as a hematologist-oncologist at C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital and continuing to work in the lab at niversity of Michigan. She has received federal funding and will be getting her own independent lab space this year.

“I think I add something to the laboratory that I’m part of. A lot of the scientists are PhD trained, but they’re coming to me when they need clinical relevance or to help with certain angles to their research,” she said. “It makes me realize that an MD person with a research background can really be an asset to push research forward, because I’m thinking about problems in a different way because of my clinical background.”

Eventually, Dr. Singh wants to bring the skills and experience she’s gained in the immunology lab back to figuring out that question she studied as a St. Baldrick’s Fellow – why do kids with DBA get cancer at a higher rate than other kids throughout their lifetime? Solving that puzzle is her long-term goal, she said.

But Dr. Singh never would have gotten started without St. Baldrick’s opening that first door and giving her the support to succeed.

“Doing research as a clinician is exceedingly difficult. You’re always pulled for time,” she explained. “Because I wasn’t trained as a PhD, I had to first learn basic techniques when I started in the lab. St. Baldrick’s really gave me that protected time, where I could learn some of the skills I needed to do research. Really, without that protected time – that support from St. Baldrick’s – I definitely would not be in research.”

But these grants aren’t just good for the individual who receives them. To Dr. Singh, having doctors contribute and learn in the lab benefits childhood cancer research as a whole – and the kids with cancer who depend on that research to stay alive.

The more minds working on the problem, the better.

“Research requires people to look at problems from different perspectives. If you’re looking at a problem from just one angle, it’s difficult for progress to happen,” she said. “I think it’s important to fund a diverse group of researchers – people who are trained in a classic, scientific way and then people who are trained to take care of patients at the bedside and who are also interested in research … Just those two groups of people meeting and working together on a problem, that’s the only way we are going to cure childhood cancer.”

Help us fund the next generation of researchers and together we can take childhood back from cancer. Donate today.

Read more about our researchers on the St. Baldrick’s blog:

SBF

Tweets »

SBF

Tweets »