Yesterday, Ambassador Phineas’ dad, Carlos, joined more than 200 childhood cancer advocates on Capitol Hill to drum up support in Washington for kids with cancer. He opened up about what it’s like to have two children diagnosed with cancer, how research saved his son’s life, and why he won’t stop telling his family’s story. Read his powerful speech below.

Carlos with his son, Phineas. Phineas was diagnosed with cancer when he was 4, six years after his sister Althea died of childhood cancer.

I live in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, but like most of my neighbors, I’m not actually from North Carolina. Chapel Hill is a college town where new people come and go every year.

Whenever my wife and I meet people for the first time, one of the first questions we get asked is, “So, how did you end up in Chapel Hill?”

When I hear that question, I always freeze for a second because I have to decide carefully how I want to answer.

Our kids are still in grade school and a lot of our social interaction is with other parents, which leads to another question that stumps me every time: “How many children do you have?”

In either case, it’s an innocent question, but the answer is complicated and the truth is probably a lot more than the person asking is prepared to hear.

When we moved to Chapel Hill in 2006, we had two little girls. My oldest daughter, Fiona, was a perfectly healthy 5-year-old. But our youngest girl, Althea, was fighting for her life.

When Althea was 16 months old, she was diagnosed with the rarest, most aggressive form of acute myeloid leukemia. We were living in Miami at the time.

Althea was diagnosed with childhood cancer at 16 months old.

Of course, hearing that your baby has cancer is a complete shock. But to make matters worse, we were told from the start that her chances of survival were not good.

Her already dismal odds were entirely dependent on a successful bone marrow transplant, but she didn’t have any good donor matches in our family or in any of the registries.

Our second-best bad option was to try an umbilical cord blood transplant.

Back in 2006, the best place you could be for a cord blood transplant was at Duke University Hospital in Durham.

We were scared and desperate, but also desperately hopeful. We knew that if somehow this actually worked, we were going to be spending a lot of time in North Carolina between transplant, recovery and follow-up care.

Learn more about childhood cancer >

Fiona was turning 5 and would need to start kindergarten in the fall. So we made the decision to go all in, sell the house in Miami, and buy a place in Chapel Hill, about 10 minutes away from Duke.

So to answer that first question, Althea had cancer, and cancer is the reason we moved to North Carolina.

“We were told from the start that her chances of survival were not good,” Carlos said.

Althea got her transplant in October 2006, but it turned out to be an exercise in futility. She relapsed two weeks after her transplant. We were told it was the quickest relapse they had seen in any of their transplant patients. Apparently, we produce exceptional children.

When it was clear that we were out of medical options, we took our baby girl home to die.

One of the harshest memories I have of that time was when we brought Althea home and got out of the car that first day. She asked about a strange noise, and we finally figured out that she was talking about birds. They don’t have birds in the hospital and she had been there long enough to forget their sound.

Althea died December 1, 2006, just 10 months after we first found out she had cancer.

Losing a child is an indescribably strange experience. Recovering from that loss is a complicated lifelong journey.

A big part of that journey for us was trying to accept our loss and focus on all the reasons we fought so hard to keep Althea alive in the first place.

Even though we knew that we could never replace Althea, we still wanted another child. We may have been insane at that point, but we weren’t getting any younger and life wasn’t getting any longer, so we went for it.

On June 7, 2008, our son Phineas was born. I won’t try to claim that having a new baby in our life took away the pain of losing our daughter, but he did give us all something new and hopeful to focus on. Bit by bit, we began to ease into a new life and things became really good again — for about four years.

“I won’t try to claim that having a new baby in our life took away the pain of losing our daughter, but he did give us all something new and hopeful to focus on,” Carlos said.

In March of 2013, Phineas got sick. Impossibly enough, it was leukemia.

Once again, we found ourselves in the emergency room watching a nurse place that first PICC line into his tiny hand as another one of our children began his battle with cancer.

At first, we were hopeful because this time around, it was acute lymphoblastic leukemia — we knew that was the most treatable kind and we liked the odds.

But after the first round of chemo, it was clear that his disease was not responding the way the doctors had hoped. He was bumped up to the “very high risk” group. Once again, we heard that our child was going to need a bone marrow transplant if he was going to have a shot at growing up.

By the second round, it was pretty clear that his disease was chemo-resistant and we were running out of options to get him into the kind of remission he needed for a successful transplant.

Things were looking grim, but in hindsight, we caught some lucky breaks this time around. Phineas’ body couldn’t tolerate a lot of the chemo that was in his protocol, so he only had a few months of highly toxic frontline treatment.

The first search of the marrow registries came back with 10 potentially perfect matches, so we knew he had good options — if we could ever get him into remission.

That summer, we caught the luckiest lucky break of all.

We managed to get him into a chimeric antigen receptor T cell trial led by St. Baldrick’s Scholar Dr. Daniel Lee at the National Institutes of Health. That immunotherapy trial saved our son’s life and opened our eyes to the future of cancer care.

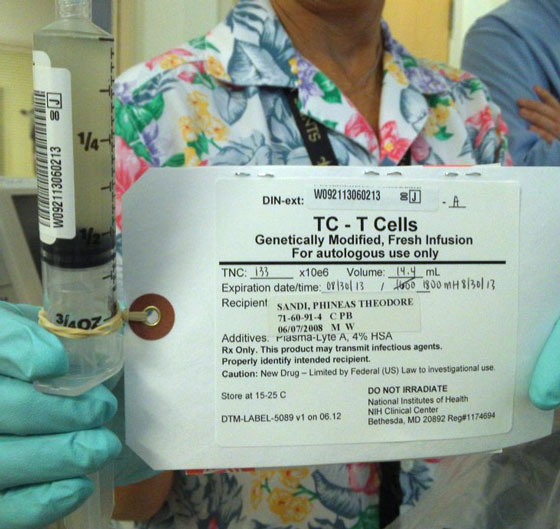

It took a month and a half to clear the red tape and paperwork to get him enrolled in the trial. It took two weeks to manufacture his modified T cells. And it took another two weeks for those T cells to destroy every detectable leukemia cell in his body.

Phineas’ modified T cells.

But it worked.

Because of this incredible breakthrough, he was able to move on to a bone marrow transplant after a two-month break from chemotherapy.

It was surreal to be taking such a strong and healthy-looking kid into transplant, but we knew, with our family history, it was his best shot at a real cure. Phineas had his bone marrow transplant in October 2013.

Today Phineas is alive and he is thriving — finishing up first grade, riding bikes, fighting with his sister, shooting hoops and playing entirely too much Minecraft. We get to celebrate his eighth birthday in three weeks.

He’s still a kid that has been through cancer treatment and he’s going to be facing the same survivorship issues as any other kid who has been through chemo, radiation and a transplant. But because of the immunotherapy research that has been going on for the last 20 years, he has been off all meds since the summer of 2014.

VIDEO: How Immunotherapy Saved Phineas’ Life >

After Althea died, we didn’t get involved in childhood cancer, pediatric hospice or any other kind of advocacy. We were angry, broken, tired people who just wanted to move on with our lives and focus as much as we could on whatever was next. I think we were able to do that by focusing on how rare and improbable her disease had been and really believing that was something we’d never see again.

Losing our child was awful, childhood cancer and the treatments for childhood cancers were awful, and we wanted to try and focus on happier things.

But when Phineas got sick, we experienced a pretty rapid conversion. We couldn’t write this off as random anymore, and we definitely wanted answers for ourselves, for our children, and for all the other affected families we were meeting along the way.

Phineas with his doctor, St. Baldrick’s Scholar Dr. Daniel Lee.

Phineas’ experience was incredibly different from the standard three-year protocol for boys with ALL. Once he got through the worst of immunotherapy and sailed through his transplant, we saw firsthand how much different cancer treatment can be. Phineas’ doctors and nurses saw it, too. We constantly heard how amazingly strong and healthy he looked so soon after treatment.

2013 was a tough year for us, but unlike the horror of 2006, Phineas was very much alive. We were profoundly grateful for the people who helped to make that happen. We wanted to be on THAT team.

Once the post-transplant dust had settled, we reached out to the doctors who had saved our son and asked them, “What can we do to help?”

The answers we got all basically boiled down to this:

Connect with the organizations that are raising money and raising awareness and tell your story to anyone who will listen. Most people have no idea this is happening.

For a lot of us cancer parents, it’s very hard to imagine making it through life with perfectly healthy children. As awful as it is, this is our normal.

For most people, though, they really mean what they say when you first tell them that your child has cancer, or that your child died from cancer. In my experience, at least four out of five people will look you right in the eye and tell you, “I can’t imagine.”

And all they’re doing when they say that is being completely honest with you. They really can’t imagine what we’ve been through.

The Sandi family (left to right): Fiona, Carlos, Phineas and Tina.

That is the reason why WE are here in Washington.

We are going to be asking the people who represent us for help with a problem that most of them can’t imagine and justifiably don’t want to imagine. We are here to break down that problem for them and make it real.

We want them to imagine.

The Alliance for Childhood Cancer has done an excellent job of making a solid, logical, articulate argument for why our representatives should support our cause. But statistics and reason are no substitute for sitting face to face with someone who has lived through this and who understands beyond what words can convey just how important this really is.

That’s something you tell people with your eyes and your presence, while they are listening to your story.

While their brain processes your words, their hearts will register how real this is.

Tomorrow, we’re going to be wandering through the halls of the United States Congress — the very center of the most powerful government that has ever existed.

We will be meeting with the people who control that power and we will be sharing some very powerful stories.

These stories have the power to change their hearts. And when we do, their hearts will tell their minds the right way to vote.

We need to connect with them, let them know who we are, let them know why we care, and ask them as our representatives, as our neighbors, and as our fellow human beings, to stop for a moment and just imagine.

Imagine what one day of our lives is like.

And then we ask them to help.

Never underestimate the power of our stories.

All we need to do is go out there tomorrow and tell them the way we have lived them, warts and all. If we are open, sincere and human, there is no way we can possibly fail.

Your voice matters — and you don’t have to go to Capitol Hill to be heard. Join advocates across the country in an online effort to get Congress to step up and support kids with cancer.

Read more on the St. Baldrick’s blog:

SBF

Tweets »

SBF

Tweets »